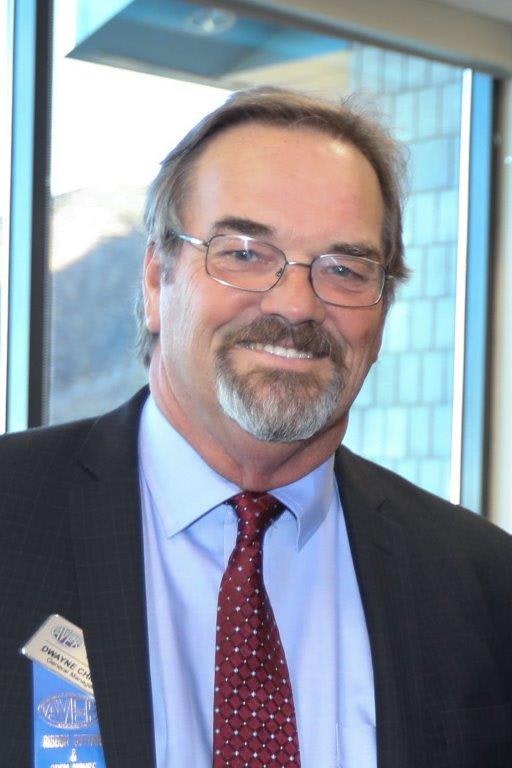

GM Report: Dwayne Chisam on State Water Project History and Long-term Water Supply

A complicated series of events have contributed to the turmoil surrounding the long-term water supply outlook for State Water Contractors, including AVEK.

The California Department of Water Resources has the authority to divert water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Construction of a water conveyance system had been discussed in the 1930s. The Central Valley Project started in 1933 as a state funded venture to manage flooding, store water and produce electricity.

During the Depression era funding became difficult and California turned that project over to the federal government. The Bureau of Reclamation took charge, considering Shasta dam as a key to the project.

Initially the concept behind the State Water Project was to supply water to arid Southern California, which had insufficient resources to keep pace with the region’s growth. The United Western Investigation of 1951 considered the feasibility of inter-basin water transfers in the Western United States, a plan that contemplated the construction of dams on rivers, such as the Klamath and tunnels that could transport water to the Sacramento River system.

It was determined that an essential element would be a statewide water management system and the California Department of Water Resources evolved in 1956. Voters passed the Burns-Porter Act in 1960 to build the State Water Project. In 1961 ground was broken at Oroville Dam. In 1963 work began on the California Aqueduct and San Luis Reservoir. At the time the pumps were built, there was a low demand for water. Planners knew the pumps were not a long-term solution.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, functioning under the auspices of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, can provide applicants with an incidental take permit if accompanied by a habitat conservation plan. An incidental take permit indicates that a lawful, but non-federal activity can result in the take of threatened or endangered wildlife.

In 1989 the Environmental Protection Agency labeled Sacramento River Chinook salmon as threatened.

In February of this year, President Trump signed a Record of Decision on federal biological opinions governing CVP water releases and California Gov. Gavin Newsom filed a lawsuit to stop the transfer of more water from the Delta to farmers.

Where does that leave the long-term water supply outlook?

There are key factors affecting the operation of the State Water Project – its long-term capability as a source of water for beneficial use and an estimate of its current delivery capacity. SWP is a major component of the water supplies available to many State Water Contractors, that’s 29 legal entities comprised of cities, counties, urban water agencies and agricultural irrigation districts. Local and regional water users have long-term contracts with the state Department of Water Resources for all or a portion of their water supply needs.

Capability of water from the SWP is significant in water supply planning and it affects the amount of water available for beneficial use. Availability of water supplies can vary. Several consecutive wet years can be followed by one or more continual dry years, including a critical drought period. Satisfactory and reliable estimates on the amount of water contractors can expect to receive in any given year – whether wet or dry – enables them to determine actions needed to meet their customer demands. That could require increased conservation, plans for new facilities or stored supplies to support a back-up plan.

Based on California’s topography, the infrastructure to convey water from its source in the Northern Sierras to its destination in Southern California makes the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta a major contributor in the delivery network.

All but five of the 29 State Water Contractors receive water deliveries by diversions from the delta – supplies pumped from the Harvey O. Banks or Barker Slough plants, including water earmarked for California’s Central Valley.

DWR and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation manage the statewide systems of water transfers, with USBR in charge of the Central Valley Project. Both entities must confront various challenges to operate their diversion facilities in the Delta. They are subject to regulations from state and federal agencies to maintain and improve the Delta’s long-term sustainability.

Maintaining the prescribed water quality that flows from the Delta to destinations in various basins, while protecting threatened and endangered fish species are factors that complicate operations at the Delta diversion facilities.

Continuing regulatory restrictions, like those intended to protect the estuary’s native and migratory fish species pose significant challenges to reliable and sustainable abilities to move water from the Delta to either the SWP or the CVP systems.

Climate change adds another threat to the situation with increasing seasonal floods and multiple years of drought as well as anticipated rises of the sea level resulting from increased temperatures.

Furthermore, there’s been some difficulty in managing salinity levels, with greater risk of salt water intrusion to the Delta, degrading the freshwater supply and ongoing subsidence at islands around the Delta, which are already below sea level and so far kept safe by a deteriorating levee system.

To deem the prospects of long-term water supplies as bleak, puts it mildly. AVEK’s saving grace is the multiple water banks that are being used as storage facilities for use when supplies from the state are minimal to none.